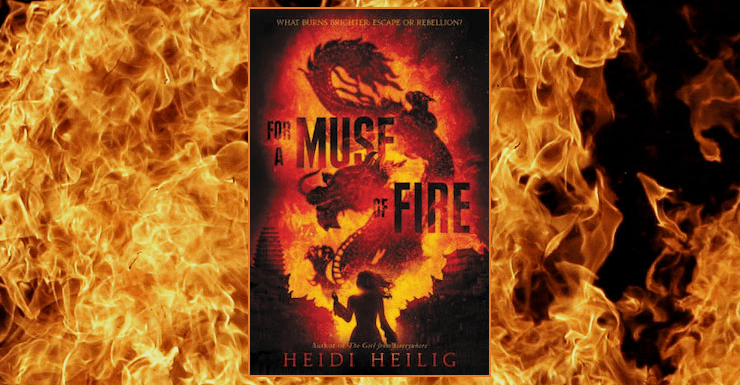

Years ago, the Aquitans crossed the sea and invaded Chakrana. Now under strict colonial rule, Chakrans are second class citizens in their own land. Compliance is demanded by a distant king, and resistance is brutally put down by the Aquitan army. Despite the odds, the Chantray family has survived, using their skills as performers to appease the colonizers and remind the colonized of their stolen traditions. They are shadow players, artists who use paper cutouts, screens, and fire to tell ancient folktales through shadow puppetry. Jetta’s brother Akra used to perform with them before he was lured away to the army by the promise of a salary big enough to send home to his family. Akra stopped writing letters a year ago. He never returned. Today, it’s just Jetta and her parents traveling the countryside, a family with no home, no village, no history, no land.

After a disastrous bid to win a trip to Aquitan where she hopes to access a cure for her “malheur,” Jetta falls into the arms of Leo, a brooding, secretive dance hall owner with ties to the rebellion. Leo also has the unfortunate luck to be the illegitimate son of the head of the Aquitan army and a long dead Chakrana woman. Despised by both groups, he is trapped in a suffocating space between two worlds. Yet he has learned to navigate the borderland by exploiting his Aquitan power to benefit the impoverished Chakrans. Guided by Leo’s sordid ties, Jetta and her parents travel to the Chakrana capital for a last ditch attempt to sail to Aquitan. Disaster besets them at every turn, and death stalks them like a shadow.

The first book in Heidi Heilig’s new trilogy finds Jetta standing on a precipice. Behind her is the only life she knows, one of shadow plays and secret magic and unfathomable loss. Just beyond her reach is the life she dreams of, a life of cures and stability and unquenchable love. The only way across the chasm is to descend into the abyss below. Her survival is not guaranteed. The journey could very well kill her. And even if she makes it through, she might still be denied her reward. But Jetta has no choice. She cannot stay on the ledge forever. Will she jump, fall, or be pushed?

Unlike other shadow players, Jetta doesn’t use strings or sticks to move her puppets but instead imbues the objects with the souls of dead animals. She can also see the souls of the dead—from the vana of small creatures like worms and bees to the arvana of dogs and cats to the akela of humans, and even the n’akela, a human soul that can possess the corpses. Necromancy is the domain of Le Trépas, an evil monk who reveled in death and terrorized his fellow Chakrans before the invaders imprisoned him in his own temple. Neither the Chakrana or Aquitans would consider her abilities as a gift. If Jetta’s secret was discovered … no, the consequences are too horrible to imagine.

Jetta is different from most other people in one other key way: her malheur. Although the phrase “bipolar disorder” is never used, it’s clear from the text (and Heilig’s author’s note) that’s what she’s dealing with. Jetta constantly mistrusts what she sees and hears. When she sees lights in the distance, are they souls? Lanterns? Hallucinations? Because no one else can see souls, it makes discerning reality from fiction that much harder. Sometimes she hears things, too, but like the lights, she often can’t tell if a soul is speaking to her, if the voice is coming from a real person, or if it’s all in her head. There’s also a subtle parallel between Jetta’s interactions with the vana and arvana and the difficulty some people with bipolar have with distractions, concentrating, and ADHD.

Heilig doesn’t shy away from pulling the reader into Jetta’s ups and downs. As she and Leo escape from the army by heading deep into the underground tunnels of the Souterrain, Jetta makes a literal and psychological descent into darkness. The days float by in a fog. She barely eats or drinks, her thoughts are as slow and sticky as molasses, and time loses all meaning. Later, Jetta also marvels to herself about how important the little things like brushing your teeth and changing your clothes can feel. I know we all like to joke about self-care, but when you’re locked in the middle of a depressive cycle, something as basic as getting up to open a window can feel like trekking up Mount Everest, and seeing the sun for the first time in ages can make you feel like a person again, even if just for a moment. Although I don’t have bipolar disorder, I do suffer from depression, and lemme tell you that whole Souterrain journey hit too close to home. Heilig absolutely nailed what it’s like.

Buy the Book

For a Muse of Fire

Eventually Jetta comes out of her depression and swings right into a manic episode. She cleans, organizes, works, does everything all at once. The extremes of the episode wane, but the fundamentals do not. She’s reckless, hyperactive, and irritable. She hardly sleeps and struggles with risk assessment. YA plots often rely on impassioned teenagers acting impulsively, but while the plot mirrors her bipolar ebbs and flows, Heilig makes sure we understand that what’s happening to Jetta is bigger than a trope or plot device. Jetta knows she cannot help her malheur, that it is a part of who she is even if it sometimes consumes her. She’s driven by the need for an Aquitan cure or treatment, and her quest will force her to ask just how much she’s willing to sacrifice to get it.

The teeming undercurrent of all this lush character work is the biting anti-colonialism commentary. Heilig takes no prisoners with her critique. Lines can be drawn between Aquitan and Chakrana and France’s occupation of Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia and America’s ill-planned war there a century later, but the novel is not a direct comparison. While the Aquitans think of themselves as benevolent overlords, their true status as invaders shines through. By not shying away from calling out those who resist oppression by oppressing others, Heilig vilifies the conquistadors without victimizing the conquered.

I cannot stress enough how impressive For a Muse of Fire is. Heilig’s characters are evocative and refreshingly unique. The action scenes are detailed enough to drop you into the middle of the fight as if you’re right there with Jetta and Leo. Peppered throughout are snippets of poetry, maps, sheet music, play scripts, flyers, telegrams, and letters that together construct a visceral, vivid world. The sheer volume of disparate storytelling techniques could easily become unwieldy and disjointed, but somehow it doesn’t. As tense at the narrative was, the ephemera carved out some much needed space. Looking in on other characters in non-traditional ways was like being able to finally take a deep breath after holding it in for several chapters.

Beyond the technical craft, Heilig has crafted a stunning epic fantasy rooted in her intersectional #ownvoices background as someone who is hapa and has bipolar disorder. The result is a nuanced, heartrending story that will leave you shattered and begging for more. I was prepared for greatness—this is Heidi Heilig after all—but it still took me by surprise. There was so much I loved about it. SO. MUCH. For a Muse of Fire is the anti-colonial, mental illness #ownvoices, POC-centered, female-led, young adult epic fantasy you never knew you wanted.

For a Muse of Fire is available from Greenwillow Books.

Photo in top image by Fir0002/Flagstaffotos – Own work, GFDL 1.2

Alex Brown is a YA librarian by day, local historian by night, pop culture critic/reviewer by passion, and an ace/aro Black woman all the time. Keep up with her every move on Twitter, check out her endless barrage of cute rat pics on Instagram, or follow along with her reading adventures on her blog.